Freely released into the cosmos every few days...

Welcome!

The essential self is innocent

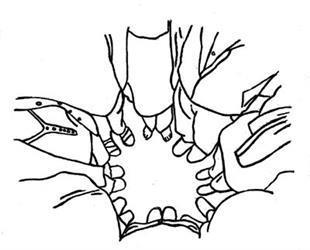

Two sensations stood out as peculiarly blissful in my childhood... The first has been alluded to: the awareness of things going by, impinging on my consciousness, and then, all beyond my control, sliding away toward their own destination and destiny. The traffic on Philadelphia Avenue was such; the sound of an engine and tires would swell like a gust of wind, the head- light beam would parabolically wheel about the papered walls of my little room, and then the lights and the sound would die, and that dangerous creature of combustion and momentum would be out of my life. To put myself to sleep, I would picture logs floating down a river and then over a waterfall, out of sight. Mailing letters, flushing a toilet, reading the last set of proofs-all have this sweetness of riddance. The second intimation of deep, cosmic joy, also already hinted at, is really a variation of the first; the sensation of shelter, of being out of the rain, but just out. I would lean close to the chill windowpane to hear the raindrops ticking on the other side; I would huddle under bushes until the rain penetrated; I loved doorways in a shower. On our side porch, it was my humble job, when it rained, to turn the wicker furniture with its seats to the wall, and in these porous woven caves I would crouch happy almost to tears, as the rain drummed on the porch rail and rattled the grape leaves of the arbor and touched my wicker shelter with a mist like a vain assault of an atomic army. In both species of delightful experience, the reader may notice, the experiencer is motionless, holding his breath as it were, and the things experienced are morally detached from him: there is nothing he can do, or ought to do, about the flow, the tumult. He is irresponsible, safe, and witnessing: the entire body, for these rapt moments, mimics the position of the essential self in its jungle of physiology, its smoldering tangle of inheritance and circumstance. Early in his life, the child I once was sensed the guilt in things, inseparable from the pain, the competition: the sparrow dead on the lawn, the flies swatted on the porch, the impervious leer of the bully on the school playground. The burden of activity, of participation, must clearly be shouldered, and had its pleasures. But they were cruel pleasures. There was nothing cruel about crouching in a shelter and letting phenomena slide by: it was ecstasy. The essential self is innocent, and when it tastes its own innocence knows that it lives forever. If we keep utterly still, we can suffer no wear and tear, and will never die. John Updike, from A Soft Spring Night in Shillington.