Freely released into the cosmos every few days...

Reflection 12

Reflection 12Welcome!

My Father

In an earlier Reflections I mentioned my father and said I’d tell you how he reacted to headlessness. Well, here’s the story. Are you sitting comfortably? Then I’ll begin…

When I first discovered headlessness in 1970 I was enthusiastic. I remember telling my father about it one day at home when I was still a teenager. I’m not sure he had actually asked to hear about it… but I decided to tell him anyway! My father was an engineer and became chairman of the firm that his father started, in Yorkshire, in the north of England. His father’s middle name, by the way, was Obadiah, a name straight out of the Old Testament and a name which I love. If I had to change my first name I would choose Obadiah! That was my grandfather. Since I’m on the subject of my ancestors, both my great grandfather and my great great grandfather, on my father’s side, each rang the bells at Liversedge parish church in Yorkshire for over sixty years. Just in case you wanted to know!

Anyway, my father was a very good engineer, and played cricket when he was young, and was also a good carpenter. But he wasn’t really a philosopher (like me, ahem…) and though my mother became an amateur actress and could recite poetry, and still does, my father was not a literary person. Suffice it to say that whether it was his lack of interest in philosophy or my clumsy way of telling him that he had no head, his response was to caution me about living in cloud cuckoo land… So I got the message and didn’t mention headlessness again for thirty years…

And then, a few years ago, I was invited to give a workshop at the Friends Meeting House in Scholes in Yorkshire, which is close to where my parents were living and where my mother still lives – my father died in 2004. The night before the workshop I was staying with my parents and my father, who was then in his eighties, was preparing dinner in the kitchen. I was helping him chop carrots. Suddenly he turned to me and said:

“Richard, what do you do in these workshops? What are they about?”

I was somewhat taken aback. There had been rather a long pause since we last spoke about this! But I felt touched as well. My father’s health was failing and though he did not speak much of dying, he was thinking about it. The thought crossed my mind that behind this question might be a much deeper one that was highly meaningful to him – what happens when we die?

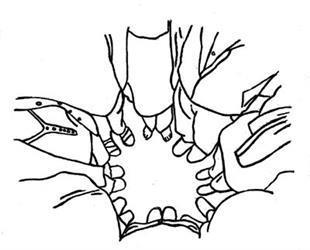

Well, we were in the kitchen chopping carrots, and he wasn’t a philosopher, and I knew that if I began to talk about ‘what you are depends on the range of the observer’, and ‘all the great mystics say that at centre you are God’… then I would lose him faster than I had thirty years before. So I replied:“Dad, it’s about noticing that from your own point of view you can’t see your own head, that you are looking out of space…” Go straight for the jugular, I thought, or rather, for what is even nearer than the jugular…

At which point my father looked puzzled, though I don’t really know what was going on in him. Nor did I find out. For at that moment my mother, also in her eighties, had arrived at the kitchen doorway, unable I think to permit any further conversation between father and son without herself being present!

My mother, bless her, is not very tall, and seems to get smaller as each year passes. Recently one of her carers asked her if she had always been so small. “No!” she replied. “I was smaller when I was a baby!” Great reply, mum!

Anyway, my mother had arrived at the kitchen doorway just in time to hear me say to my father that you can’t see your own head. She stood at the doorway and declared simply and authoritatively:

“Yes, above here [her hand at neck level] it’s just open.”

I said, “That’s it mum”, and thought: You’ve got it completely. You can’t see it more clearly or deeply than that.

There was then a moment’s silence, after which my father continued cutting the carrots, and so did I, and I think we might even have started talking about football or cricket! I guess in that moment I sensed that it just wasn’t my father’s cup of tea.

Now my mother had not, as far as I can tell, conscientiously been paying attention to who she really was during the many years since the time she met Douglas Harding back in 1970 – she had visited Douglas with my brother and I several months after my first meeting with Douglas. She was well aware that headlessness was very important to her sons, but it turned out not to be something that was on the front burner for her. Nevertheless she had had the good fortune, grace, curiosity, intelligence, whatever it was, to have actually LOOKED all those years ago when my brother and I first discovered headlessness. Thirty-odd years later, at the kitchen door, she LOOKED again. (I’m not saying she hadn’t LOOKED in between times - I don’t know.)

Was my mother’s LOOKING at that moment any less deep or clear or boundless than mine, just because she had to a degree neglected it in the intervening years? No! How could it be? How could one person see no-thing more clearly or less clearly than another person? Impossible. (Who is seeing the no-thing, anyway!) The difference comes of course in how you respond to what you see, not in what you see.My father didn’t LOOK. Or, my guess is, he did. But he quickly shied away from it, for whatever reason - and the reasons we don’t keep LOOKING can go very deep. But did that mean he was not living from the space, from who he really was? Of course not. Everyone is living from here. Some of us are simply choosing not to notice it, that’s all.

So it doesn’t really matter to me that my father was not interested, at least on the surface, in noticing that he was capacity for life. Well, that’s not quite true. I would have loved him to embrace it. I think it would have helped him face death with greater peace. But I also recognize something absolutely wonderful about this whole business - that when I see the Source I am doing this as and for others. Whatever the nature of another person’s response , there is never any separation here. Not even death can divide us at this level.

One last thing: Douglas Harding once said to me that you can’t talk people’s heads off, you can only love them off. I thoroughly agree – though I don’t always remember his wise words!

Warm regards,

Richard

Send your comments to Richard

back to top